Introducing The Vaults at 40 Wall Street

Tucked away in one of the most iconic buildings in all of Manhattan and only steps from the New York Stock Exchange are the newly designed Vaults at 40 Wall Street.

Subscribe to our newsletter and be the first to know about special announcements, exclusive offers, event invitations and breaking news from The Trump Organization (i.e. Trump Hotels, Trump Golf, Trump Store, Trump Winery, Trump Commercial, Trump Realty, Trump Dining & Entertainment, Trump News & History, etc).

The idea that the game of golf was started by having a shepherd using a wooden crook to knock a rock into a hole is imaginary at best; and besides, a rock is not a ball. But over the centuries, apparently man got quite a thrill out of striking a circular object on the ground and then chasing after it to a final target such as a wall, a door, a tree or a hole.

But what was the composition of the “circular object” that they used for this pleasure? For some games, including early golf, it was most likely a wooden ball or a leather covered ball stuffed with animal hair. After using a variety of balls up to around the 1500’s, the game of golf as we know it started employing a ball made of a circular leather pouch that was stuffed with feathers and rightly called a “featherie.” The ball was round (though not perfectly so), firm and elastic. It achieved pleasing distance so that by the 1800’s it could be driven from 180-200 yards or more by a skilled player.

The production of the featherie is a story in itself. Three pieces of leather were first heavily soaked in water, then stitched together and folded inside out while leaving a small hole. Into that hole were stuffed wet boiled feathers until totally full. When the leather dried, it shrank as the drying feathers expanded, producing a compact well-shaped ball with a tight smooth surface.

Feather ball makers often succumbed to lung disease as they worked in an atmosphere with feathers floating in the air, inhaling them while completing the task. When asked what kind of feathers were used, I offer this comment: “It depends upon how high you wanted the ball to fly. If you want it low you would have chicken feathers; and if high, then duck feathers.” And now you have been amused.

But there were problems with the featherie. Heavy rains, not uncommon in the British Isles, could soften the leather during play, increasing the weight, and shortening the ball’s distance. Also, an improper strike at a vulnerable spot on the ball with an iron club could produce a face full of feathers. Lastly, and the most important fact for the growth of the game, is that it took a professional ball maker a ten-hour workday to produce just two to three good featherie balls. That made the cost of buying one, yes just one, three days of an average working man’s wages. Because of the cost of a featherie ball, golf was considered to be a “rich person’s” game.

In 1843, however, a happenstance event changed the game forever when Dr. Patterson, a theology professor at St. Andrews University, received a package from Singapore containing a statue of the Hindu God Vishnu. It was packed in the shavings of a rubbery substance known as “gutta percha,” a product of the sapodilla tree in Malaysia. Dr. Patterson’s son Robert discovered that this material could be heated and shaped, which would then harden when left to dry.

As a St. Andrewan, Robert’s mind turned immediately to the possibility of using this material for a golf ball. His early experiences produced only minor success. When Robert left permanently for the United States, his brother John took over. There were more failed experiments, but over time came encouraging improvements with the creation of ball molds. By 1846, the Patterson’s New Composite Patent ball was offered to the public at a show in London. However, it created little interest. Meanwhile, back in Scotland, golf professionals were starting to play with it. While the name “Patent” was on the ball, no such patent existed, so former feather ball makers started legally making gutta percha balls in large batches with the use of molds. By the 1880’s there were over 30 “guttie” ballmakers in Scotland.

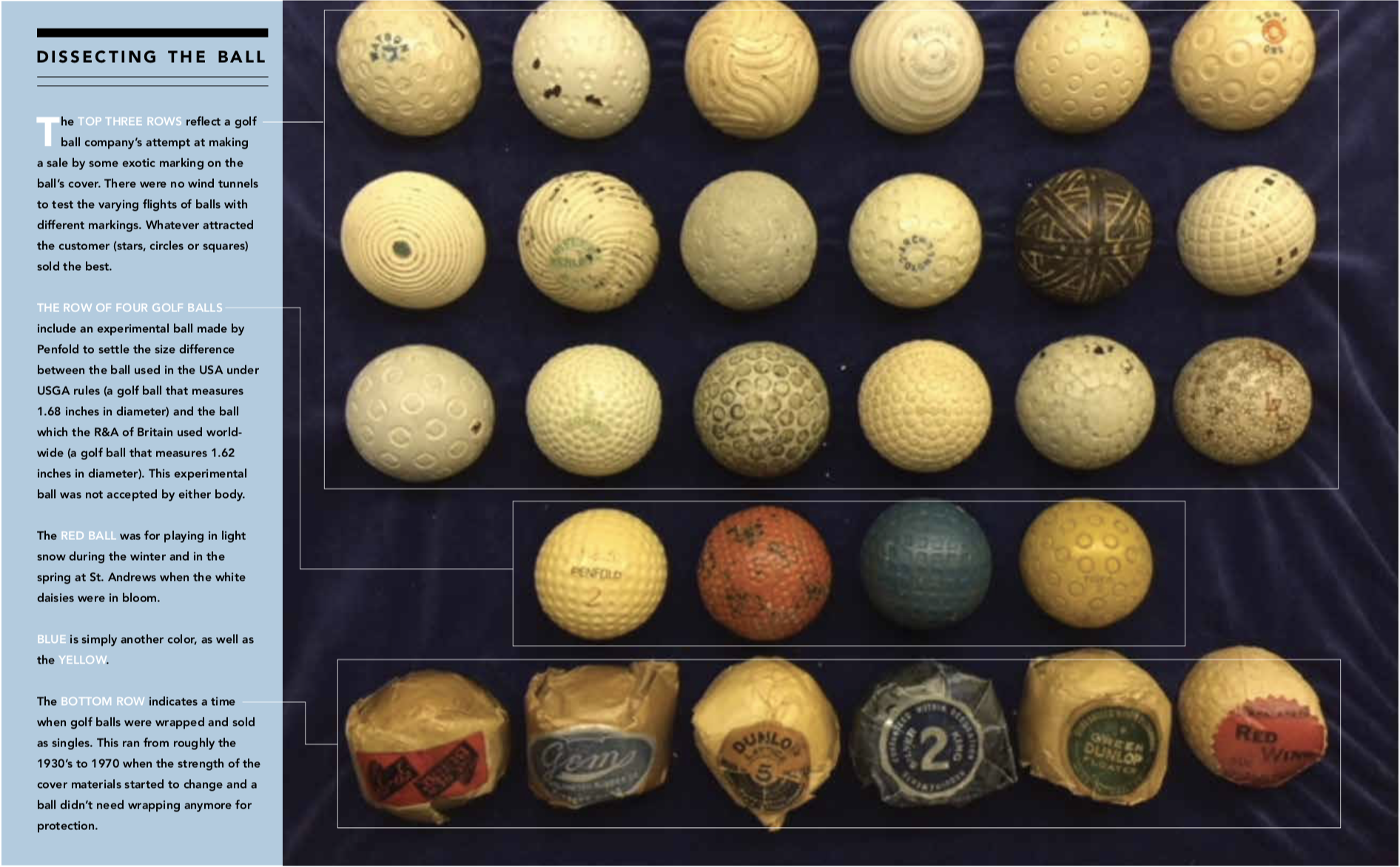

One early drawback to the first “gutties” was that they were smooth so did not hold paint well nor did they have adequate spin to provide sufficient lift. That is, until the ball was played several times absorbing cuts, which actually made the ball fly better (a ball needs a surface with markings in order to create spin). The challenge to find the exact best size, shape and depth of markings to produce optimum flight and distance still exists today.

Then in 1898, the next big event happened in golf ball history: the invention that came to be known as the Haskell Ball, named after it’s co-inventor, Coburn Haskell. Haskell was visiting the Goodyear rubber factory in Akron, Ohio to play golf with the manager, his friend, Bertram Work. As he was waiting, he saw a pile of rubber thread and got the idea to wind some of it into the shape of a ball. When he bounced that on the floor it went almost to the ceiling. With that result, he realized this might be the answer for a new golf ball.

Later, Haskell hand-wound a large roll of the rubber string around a small core, had a gutta percha cover put on it, and took it to the professional at his local club. Going to the first tee he asked his pro to hit the ball that looked just like a “guttie.” The ball carried some fairway bunkers on the fly traveling 30 yards longer than had it been a real “guttie.” The professional exclaimed, “What was that?” The answer he received was, “That is the new golf ball.”

With Bertram Work as his co-inventor, the ball came on the market in 1899. The demand was greater than the supply as each ball had to be hand wound. That is, until an employee from the Goodyear factory named John Gammeter invented a winding machine that could produce large numbers beyond any manual attempts.

Concurrently, Harry Vardon, the greatest golfer of that time and six-time Open Champion, signed a contract with the Spalding Company to put his name on their new gutta-percha ball, the Vardon Flyer. He was the first athlete in the world to receive a sports endorsement contract. In 1900, Vardon came to the United States to promote the ball by playing 89 exhibition matches throughout the country, losing only one. In addition, he won the U.S. Open in that year, all great for promotion for the Vardon Flyer. But the “guttie” days were numbered. Golf Hall of Famer Walter Travis won the 1901 U.S. Amateur using the new Haskell ball. In 1902, Vardon sent a letter to the USGA asking them to make the Haskell ball illegal because of its added distance. The “hot” ball was going to force golf facilities to lengthen their courses, plus it will cost more to build and maintain them.

One of the next innovations for the golf ball was the markings. In order to have lift, the ball cannot be smooth, as the gutty ball makers discovered earlier. So, over the next few years, ball makers started experimenting with all varieties of marks and patterns. In 1905, a Mr. William Taylor conducted experiments that showed dimplings provided the best results. He sold his patent to Spalding, who required any ball maker that used the dimple pattern to pay them a royalty. Some did, but others were forced into making creative designs until that patent expired.

Oddly enough, the next big change in ball manufacturing from just after the 1900’s didn’t come until the 1960’s when the ball historically seemed to reverse itself. It dropped the rubber thread windings of the Haskell and went almost back to a solid ball just like the gutta percha of over a hundred years earlier but with more effective material. James Bartsch, an MIT graduate, submitted a patent for a one-piece golf ball he developed by mixing thremoplastice polymers. The Bartsch ball was not a commercial success, so he joined with the PCR Company to create the Faultless ball. Better than the Bartsch ball, it was uncuttable and shorter on distance, but sold well because of its affordability.

A few years later, the Spalding Top Flite became the king of solid core balls and is still on the market today. Currently, ball construction is now totally focused on the layered solid core-style with gradual innovation and improved design, which also increases distance. It is not difficult to understand why Harry Vardon wanted to restrict the ball’s flight to protect the game. But who doesn’t want to hit the ball farther?

As a member of six Golf Halls of Fame, including the world-renowned PGA Hall of Fame and the World Golf Teachers Hall of Fame, Gary Wiren has taught over 250,000 people in private, group and seminar settings in 30 countries.

As Director of Golf Instruction at the award-winning Trump International Golf Club, West Palm Beach, Wiren holds a number of prestigious accolades: he was a collegiate conference champion, won the South Florida Seniors PGA title and the South Florida long-driving championship, played in the USGA Senior Open and the PGA Senior Championship, and has also won the World Hickory Open Championship. Wiren also holds honorary memberships and distinguished-service recognition from Sweden, Italy, New Zealand and Japan.

In addition to the multiple accolades he has won, Wiren has written or participated in the writing of over 250 magazine articles and 14 books, including the most influential book on golf instruction: The PGA Teaching Manual. His very own award-winning book, When Golf Is a Ball was selected as the “best golf book in the year 2004.”

Tucked away in one of the most iconic buildings in all of Manhattan and only steps from the New York Stock Exchange are the newly designed Vaults at 40 Wall Street.

On behalf of the Trump family and The Trump Organization, we wish you a very merry Christmas and happy holiday season! As 2023 comes to a close, we'd like to take this time to pause and reflect on some of the amazing accomplishments and milestones our organization has achieved over the last 12 months.

Discover luxury redefined at Trump International Hotel & Tower Chicago, named a Five-Star Hotel in Forbes Travel Guide's prestigious 2024 Star Awards. Experience unparalleled elegance and world-class service at our acclaimed five-star hotel in Chicago and indulge in a truly unforgettable experience.